This website use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website

P.IR.A.M.iD

2023-1-ES01-KA220-VET-000157060

Cooperation and Multiculturalism: Lessons from Sherif’s Experiment

18 September 2025

In multicultural contexts, conflicts can emerge easily, and cooperation is not just a matter of goodwill; it requires effort, attention, and structured conditions. How can we understand which factors promote cooperation and which fuel hostility? A famous psychological study, the Robbers Cave experiment conducted by Muzafer Sherif and colleagues, provides valuable insights.

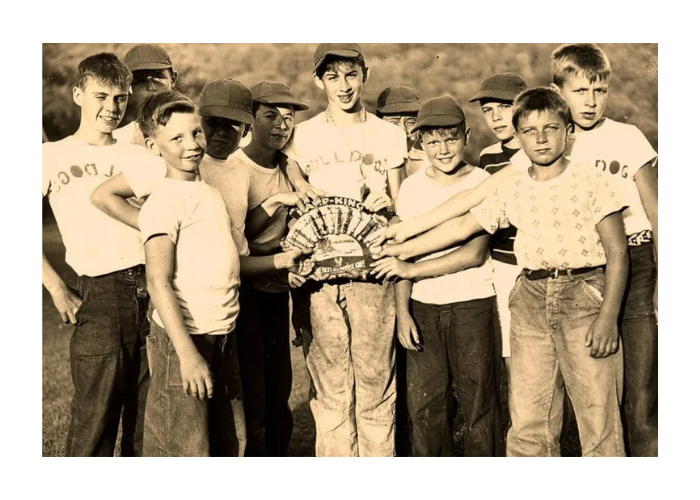

In the experiment, 22 boys were divided into two groups, the “Eagles” and the “Rattlers,” who initially did not know each other. In the first phase, each group engaged in activities to build internal cohesion, developing group identities, rules, and hierarchies. When the groups were later put into direct competition through games and challenges in which only one group could win, hostility, stereotypes, and aggressive behavior quickly emerged. Only when superordinate goals were introduced—tasks that neither group could achieve alone and that required collaboration—did tensions decrease and positive relationships develop. These included practical challenges that required pooling resources and working together to solve common problems. The experiment demonstrated that cooperation on shared goals fosters empathy, reduces prejudice, and promotes positive interactions.

The lessons from Sherif’s experiment can be applied to real-world multicultural contexts, where groups often carry history, experiences, and pre-existing biases. Cooperation is most effective when common goals are identified that require all participants to contribute, and when contact between groups is combined with concrete collaborative activities. Collective challenges such as environmental protection, safety, education, or community projects can play the same role as the superordinate goals in the experiment. At the same time, it is important to pay attention to spontaneous biases that may arise when groups perceive competition or threat, and to actively address them.

In short, Sherif’s work shows that positive intercultural relationships are not automatic; they require structured conditions, shared objectives, and visible opportunities for collaboration. By creating environments where groups must work together on meaningful tasks, awareness of differences can transform into trust, empathy, and genuine cooperation, allowing multicultural groups to overcome misunderstandings and hostility and to build inclusive and harmonious relationships.

practical challenges that required pooling resources and working together to solve common problems. The experiment demonstrated that cooperation on shared goals fosters empathy, reduces prejudice, and promotes positive interactions.

The principles highlighted by the experiment can also be applied in contexts where groups already carry history, experiences, and prejudices, as is often the case in multicultural settings. Cooperation works best when common goals are identified that require all participants to contribute. Collective challenges such as environmental protection, safety, education, or community projects can serve the same role as the superordinate goals in Sherif’s experiment.

At the same time, learning to understand others, listen to cultural differences, and respect them is fundamental for building strong relationships. However, these behaviors are most effective when paired with concrete collaborative actions, because only through shared experiences can awareness of differences turn into trust, empathy, and real cooperation. In this way, as the experiment demonstrates, multicultural groups can overcome misunderstandings and hostility, build positive connections, and promote a more inclusive and harmonious coexistence.

This project has been funded with support from the European Commission.

This publication reflects the views only of the authors, and the Commission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein.